|

Child Looking at Brontosaurus, American Museum of Natural History, 1937. |

HANK's posts (here and here) on research methods have got me thinking about the craft aspect of what we do. But I'd like to take the discussion in a slightly different direction and ask what happens if we stop assuming that we historians ought to be primarily in the business or writing texts.

In my research, I think a lot about the different effects that various media have on us as consumers of culture. For example, I have found that fully articulated, free-standing displays of mounted dinosaurs in the late 19th and early 20th century are best thought of as mixed media installations. In addition to fossilized bones, lots of other materials were required to mount a dinosaur, including shellac, gum acacia, paint, plater of Paris, and iron or steel. Moreover, mounted dinosaurs were almost always paired with other ways of representing prehistory, including three dimensional models and paintings of these animals in the flesh.

|

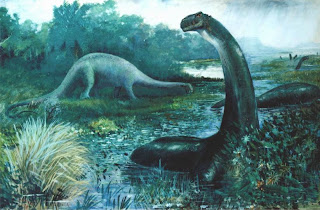

| Brontosaurus displaying characteristically turn-of-the-century amphibious habits in a painting by Charles Knight, under the direction of Henry Fairfield Osborn. |

There are a number of ways we can go about making sense of mounted dinosaurs as mixed media sculptures. I like to think about the various strengths and weaknesses of each medium. For example, paintings and three dimensional models are a good way to put life into dead bones, to use a phrase of which my historical actors were very fond. They literally helped visitors interpret the fossils on display, showing them how to visualize these animals in the flesh. At the same time, the fossils served as a reminder that these visualizations were not mere, idle speculation. They were grounded in material traces that survived from the actual past.

|

| Mounting Brontosarus at the American Museum, 1904. |

In addition to a mixed media sculpture, mounted dinosaurs were a form of publication. Many decisions (often controversial ones!) had to be made when putting a dinosaur on display. For example, when Curators from the American Museum of Natural History mounted a Brontosaurus in 1905, they took a wager that it held its legs erect under its belly, like modern elephants do. This was by no means a foregone conclusion at the time, and several paleontologists, including Oliver Perry Hay from the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C., and Gustav Tornier from Berlin, objected. They thought it more likely that dinosaurs held their legs sprawled out at a ninety-degree angle, like modern lizards and crocodiles.

|

| Illustration of sauropod dinosaur Pose by Mary Mason, under the direction of Oliver Perry Hay, Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences, 1910. |

In the past two or three decades, we historians have become reasonably used to (and, I hope, good at) analyzing non-textual sources. But, unlike the paleontologists that I study, most of us continue to use words as the principle (if not only) way to communicate the fruits of our research. We historians write a lot of books and deliver even more lectures. But we rarely curate exhibits or make images. Why should this be the case?

I see no reason it should!

There are some encouraging signs of things moving in a new direction. Several historians of science I know of, including Peter Galison and Hanna Shell, use documentary film as a form of publication. But what other media might historians use to communicate with one another, and with a broader public?

One thing I've been especially interested to explore in my research is the relationship between elite science and popular culture. So, I have a soft spot for 19th century sites of amusement that blur the boundary between the two, especially those that throw in some humbug for good measure.

Dime museums, like PT Barnum's museum, which used to be located on Broadway and Anne Street in New York, are a particular favorite of mine. So I was super excited to visit the Spectacularium in Coney Island this weekend. This is a re-creation of a 19th century Dime Museum (of which there were several in Coney Island), that exhibits a number of period photographs, playbills, and guidebooks, in addition to some taxidermy and other exhibits. (Most of the latter were acquired when one of the last Dime Museums, on the Canadian side of the Niagra Falls, finally shuttered its doors a few years ago.)

I also discovered that Coney Island Museum still runs a sideshow. Here, you can see a snake charmer, a mesmerist, a strong man, and other remnants of the 19th century stage now usually only found in the circus.

Moreover, there is an excellent website and live gallery exhibit, the Moribund Anatomy, located near the Gowanus canal in Brooklyn, for those of you into 19th century medical museums. Am I alone, or does anyone else see these as a call to arms?

2 comments

Agreed: there's no reason why it *should* be the case, but the incentives are definitely stacked against those of us who would like to do more of this sort of thing. The way the university currently works, publications count and basically any time you spend that detracts from that output counts against you. There've also been conversations around here in the environmental history community about about how film (or other projects that could better reach a broader audience) might substitute for a book-form dissertation, and whether it should. I've got mixed feelings about that, but on the whole, I'd love to see "publication" broadened.

This post makes me think of Radiolab http://www.radiolab.org/ which has done an incredible job of dealing with history-of-science-type subjects in an audio, podcast format. Sound, as well as the visual, is a rich domain to be explored. And regarding Megan's point, I agree that the incentives are stacked against traditional publication. But I've started thinking of these multimedia endeavors as tactical interventions to be weilded in concert with, not instead of, journal articles.

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.